Deprecated: stripslashes(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($string) of type string is deprecated in /mnt/efs/html/wp-content/plugins/template-scripts/src/AuthorBios/Frontend.php on line 129

Navy, NASA want to renew Kaua‘i leases – West Side locals show support, opposition

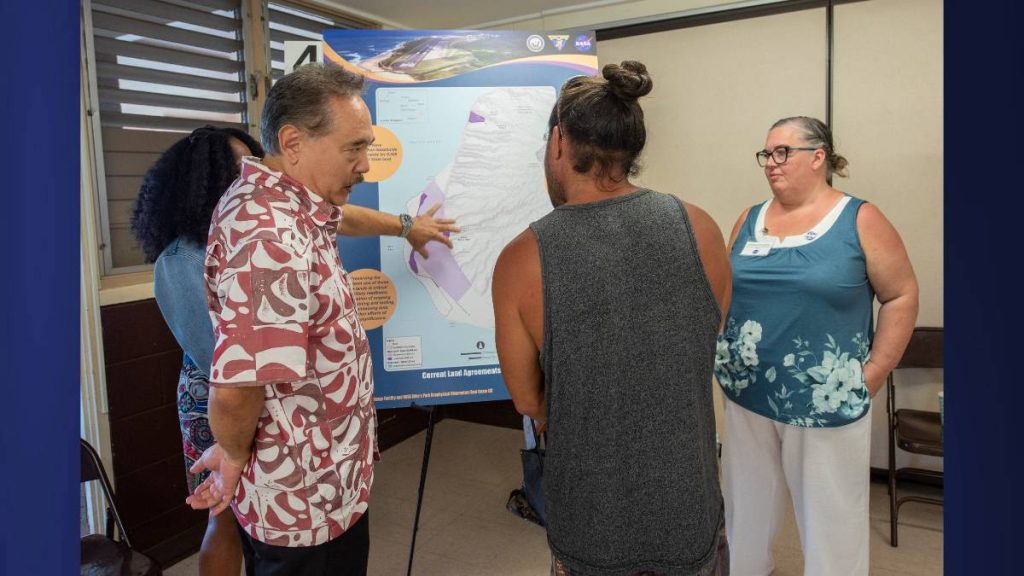

Representatives of the US Navy and NASA entered the Kaua‘i community last week – soliciting questions, comments and concerns during a three-night run of public scoping sessions held at locations across the Garden Isle.

The three meetings marked the beginning of a two-year process to create an environmental impact statement covering West Side lands the state of Hawai‘i has leased to the Navy and NASA since the mid-1960s: namely, the Pacific Missile Range Facility on Barking Sands and the Mānā Plain, and the Kōkeʻe Park Geophysical Observatory within Kōke‘e State Park.

The sites’ 65-year real estate agreements expire in 2027 and 2030, and both the Navy and NASA want to maintain their operations on Kaua‘i.

The environmental impact statement – pursuant to both the National Environmental Policy Act and state law – will be used by the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources when it decides if and how it will enter into new land deals with the maritime armed forces branch and the independent federal agency.

Capt. Brett Stevenson, commanding officer of PMRF, put his best foot forward during the public scoping session held at the Kekaha Neighborhood Center on June 5. Located on the West Side, it was the meeting held closest to the land under discussion. The sessions on June 4 and 6 were held on the more densely populated East Side, in Līhu‘e and Kapa‘a, respectively.

“This meeting here tonight is the beginning of an ongoing conversation with all of you to shape the environmental impact statement process so that we can consider your mana‘o (ideas, beliefs, opinions), your thoughts, things that are important to you,” Capt. Stevenson told an audience of approximately 30 community members. “We couldn’t do this without all of you here tonight …

“My most sacred kuleana (privilege, responsibility) here is to protect, preserve not just the Mānā Plain but across Hawai‘i and throughout the Pacific. I view this as a spiritual bond that must be continually renewed,” he continued. “I view this evening tonight as an opportunity for us to continue the work that we’ve started here to renew those vows, these leases, to help us do our work safely and effectively.”

About two dozen Navy and NASA personnel staffed nine displays arranged throughout the Kekaha Neighborhood Center. Each station was dedicated to a specific topic, ranging from the federal and state regulatory mandates governing the environmental impact statement process, to potential environmental impacts to several resource areas – including archaeological and historic resources, cultural practices, air quality and greenhouse gases, water resources and more.

At the real estate display, personnel confirmed Hawai‘i’s original long-term leases allowed PMRF and NASA the use of a combined 8,731 acres on Kaua‘i – all for the sum of $1. But those days are gone: Going forward, any negotiations will be based on the fair market value of the land.

Members of NASA explained their agency employs a staff of seven at the 23-acre Kōkeʻe Park Geophysical Observatory. The team is tasked with collecting reams of data pertaining to the Earth’s rotation, orientation in space and more. That data is sent to the US mainland every 24 hours, where it’s used to determine information vital to the performance of ubiquitous applications like GPS. (The observatory is also used by entities including PMRF and the state.)

Lifelong West Side residents expressed support, skepticism and opposition to the Navy and NASA’s presence on Kaua‘i during the June 5 meeting.

Steven Pereire of Hanapēpē is a 30-year employee of PMRF, where he works as an electrical engineer.

“They’re doing good things out there. I can say as a resident – I was born and raised here – the stewardship of the land is top-notch,” Pereire said, noting he would like to see the Navy base continue for decades to come.

“They pay a very decent wage, and with the way the cost of everything on this island goes – goods, rent, housing – it’s very hard to stay put here,” he continued. “I’ve seen so many people leave because they just can’t afford to make ends meet now, but the base is good. It gives people that stability, economically.”

PMRF frequently touts itself as the largest “high-tech employer” and third largest overall employer on the island of Kaua‘i. Of the approximately 1,000 personnel on base, 80 are military and 100 are government civilians, according to Capt. Stevenson, who claimed the remainder are people from Kaua‘i.

The Navy operates on just 410 acres of the Garden Isle; the remaining land is used as buffer zones, conservation areas, infrastructure and access corridors. The bulk of the Mānā Plain is used for agriculture, mainly by major agribusinesses Corteva and Hartung Brothers, which grow seed crops like corn and soybeans.

Capt. Stevenson likened PMRF – the world’s largest instrumented multi-domain training and testing facility – to a football stadium and military who train there to football players. Athletes often study tapes of recent games to figure out what worked and what didn’t.

“With that in mind, think of the range at PMRF like a stadium that goes from the seafloor all the way up into orbit,” he said. “That allows us to provide the high-def instant replay for the folks that come to the range to train or test new capabilities.”

Peleke Flores of Kaumakani expressed an air of measured concern while attending the Kekaha public scoping session. He paused while writing a lengthy comment to share his thoughts, claiming he arrived with many questions.

“I came … for our culture and our ʻāina (land) but also our people. How are we going to be [represented] within this planning session for the next 65 years? Are our kids?” Flores said, noting the Navy and NASA appeared to highlight “the birds, the animals, the plants … but not too much talking about the people.”

Flores, who restores traditional Native Hawaiian food systems like fishponds, is especially interested in the agricultural land surrounding PMRF.

“Can it be connected more to NHOs (Native Hawaiian organizations) or an ʻāina-based organization trying to restore that space to before the plantation period?” he asked. “A lot of information goes to the plantation period … You’re trying to keep fixing a messed-up system that wasn’t good to begin with. Go back a little further, to the 1700s, to see what that space used to be like.”

The Mānā Plain was one of the largest seasonal wetlands in the Hawaiian Islands prior to the early 1900s, when plantations drained and converted the area to lands more suitable to their methods of agriculture.

Chris Ka‘iakapu of Hanapēpē has fished, surfed and otherwise accessed West Side lands his entire life.

“The first ʻopihi (limpet) I ever picked was out on Mānā Plains. The first lobster I ever grabbed was out in Mānā, and that was prior to them restricting access after 9/11. Now it’s extremely limited access,” Ka‘iakapu said. “I don’t think the US military, the Navy, has done a good job. I don’t think they have a good track record in Hawai‘i. So it’s very hard for me to trust.”

Ka‘iakapu is a self-described Hawaiian national who believes the US military has no lawful right to occupy space within the islands. He cited “destruction widespread across Hawai‘i,” including US armed forces’ role in the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and – more recently – the 2021 crisis at the Red Hill Underground Fuel Storage Facility on O‘ahu, which saw jet fuel leaks contaminate water reportedly utilized by nearly 10,000 households around Pearl Harbor.

“I don’t support their activities out at PMRF. I think it’s upholding the genocidal war machine that is the US military. I don’t support it and I don’t think it has a place in Hawai‘i, which is a peaceful place,” Ka‘iakapu said. “I think it’s a paradox to try and do an environmental impact assessment and survey when the United States military is the most destructive force on the entire planet.”

The environmental impact statement now underway is scheduled for completion in spring 2026. Before then, the Navy and NASA will conduct another round of public engagement in spring 2025, when the Kaua‘i community will have an opportunity to read and comment on a draft version of the document.

The statement will include responses to every comment submitted during the current scoping period, which ends June 17. At the Kekaha Neighborhood Center, the Navy and NASA collected both written and oral comments; the latter were compiled by a court reporter.

Kerry Ling of NAVFAC Hawai‘i – a service provider to Navy operations in the region – is the PMRF and Kōkeʻe Park Geophysical Observatory environmental impact statement project manager.

Ling, a resident of the Big Island, claimed all Navy personnel assigned to the environmental impact statement live in Hawai‘i. Several, she added, are Kaua‘i residents with multigenerational ties to the island.

“Your comments during this phase will help the Navy and NASA understand the community concerns regarding the proposed action and also the planned analysis,” Ling told the same audience addressed by Capt. Stevenson. “Your comments will help us to determine what should be studied in the EIS, including the alternatives to be analyzed.”

Later, Ling urged Kaua‘i residents to express their concerns and questions in comments made as specific as possible, in order to ensure comprehensive and productive answers.

“I want people to know that people who care are reading these,” she said.

For more information about the PMRF and Kōkeʻe Park Geophysical Observatory environmental impact statement project, visit PMRF-KPGO-EIS.com.

To submit comments regarding the environmental impact statement:

- Visit the project website at PMRF-KPGO-EIS.com;

- email info@PMRF-KPGO-EIS.com;

- or mail a letter postmarked by June 17 to the following address:

Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command, Hawaiʻi

Environmental OPHEV2

Attn: PMRF and KPGO RE EIS Project Manager, Ms. Kerry Wells

400 Marshall Road, Building X-11

Pearl Harbor, HI 96860

Sponsored Content

Notice: Function the_widget was called incorrectly. Widgets need to be registered using

register_widget(), before they can be displayed. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 4.9.0.) in /mnt/efs/html/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6114