Big Island botanical artist’s endangered Hawaiian hibiscus featured in UK exhibition

An iconic emblem of Hawai‘i – the hibiscus flower – is spending June celebrated by an island far away from the Pacific Ocean, thanks to an artist inspired by the Aloha State’s native plants.

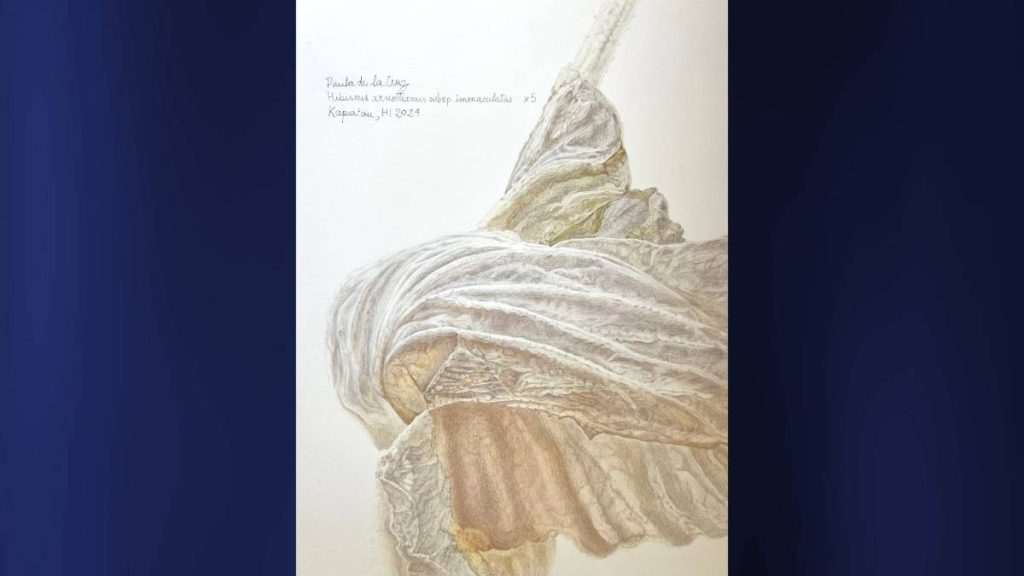

“Gloria,” a painting by Big Island resident Paula de la Cruz, appears in Plantae 2024, a prestigious exhibition of the Society of Botanical Artists in the United Kingdom. The show – held online this year – opened June 1 and will close at the end of the month.

The piece depicts Hibiscus arnottianus subsp. immaculatus, also known as aloalo, hau hele, kokiʻo kea, kokiʻo keʻokeʻo, pāmakani and the Molokaʻi white hibiscus. It is an extremely rare plant with a natural range limited to about four valleys on the island of Moloka‘i located between Maui and O‘ahu.

“When I moved here and started learning about the history of cultural and nature devastation of the islands I wanted to learn more about their native forests and ethnobotany,” said de la Cruz, who made Kapaʻau in North Kohala her full-time home several years ago.

Through her research, de la Cruz found an absence of information regarding the native plants in the forest that once occupied her community, which is now pastureland. So she dug deeper – yet visits to local residences only revealed gardens landscaped with non-native flowers. Even plants sold as “native” at certain nurseries proved not to be.

Eventually, de la Cruz discovered Hui Ku Maoli Ola, an O‘ahu nursery dedicated to truly native plants. Its vibrant collection of Hawaiian hibiscuses inspired de la Cruz to make the group, several members of which are endangered, her muse.

“I thought, ‘Well, I can’t draw every genus that is in danger,’” de la Cruz recalled. “‘Why don’t I start with something as ubiquitous as the flower of Hawai‘i?’”

There are seven species of hibiscus native to Hawai‘i, with flowers boasting a variety of colors including white, red, orange, and purple. The petals of the islands’ state flower, maʻo hau hele or Hibiscus brackenridgei, are a vibrant yellow.

“Gloria” – created using watercolors, colored pencils and silverpoint – is just the second image in a triptych illustrating the lifespan of the Hibiscus immaculatus flower, which lasts only 24 hours. It is framed by “Timida,” in which its white petals have yet to burst open, and “Modestia,” in which the petals are crumpled and the once-erect staminal column droops.

De la Cruz creates art with a sense of purpose. She wishes to draw attention to the silent lifeforms that make up 80% of the total biomass on Earth, a planet now in upheaval as a result of climate change.

“What is the role of botanical art today? On a warming planet, the role is to communicate the beauty in the quiet world of botany,” she said. “It’s very easy, I think, to get someone excited to go on a safari in Africa, because you see lions, you see elephants, that is exciting. But we’re so used to seeing plants as a green background we don’t even notice.”

De la Cruz only recently became a full-time botanical artist. The Argentina-born woman worked in advertising in New York City until Sept. 11; in the wake of the attacks, she decided to continue her education and entered a two-year program at the School of Professional Horticulture at the New York Botanical Garden. There, de la Cruz was introduced to the world of botanical art when she encountered a fellow student holding a drawing of a pineapple.

De la Cruz was immediately “smitten” with the art form and has studied it ever since. During years spent as a journalist writing for publications including The New York Times, WSJ Magazine and Air France, she covered “the intersection between travel, botany and art.”

The Kapaʻau resident, who is working with a marine biologist on a native limu (seaweed) project, now hopes to make the leap from botanical art to botanical illustration. It’s an arguably even more specialized field in which illustrators work hand in glove with scientists to document new species or create florae – treatises listing plants of a given area or period.

David Lorence is a taxonomist and senior research botanist at the National Tropical Botanical Garden on Kaua‘i who has named and published approximately 160 new tropical plant species, subspecies and varieties from across the globe. As a result, he has collaborated with botanical illustrators throughout his long career: His most recent book – the two-volume, 1,137-page “Flora of the Marquesas Islands” co-authored by Warren Wagner of the Smithsonian Institution – features hundreds of images by the esteemed Alice Tangerini.

Tangerini, an idol of de la Cruz’s, is well-known for observing and capturing details unnoticed by scientists documenting the very same plants. A species of bromeliad, Navia aliciae, was named in her honor as a result.

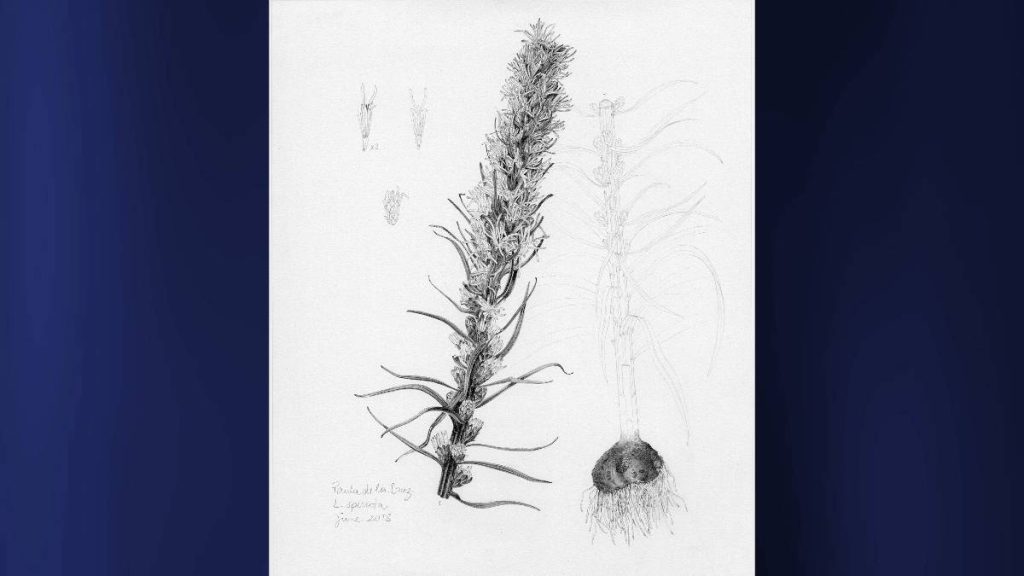

Botanical illustrators may freelance or be employed as staff members at scientific institutions, according to Lorence. Most of their work consists of black-and-white ink compositions, however, full-color pieces are not unknown. Lorence indicated this trend is due to the mundane reality of financial constraints. Pen-and-ink is less time-consuming than other mediums and therefore costs less.

“Us poor taxonomists, you know, we don’t have unlimited resources at our disposal,” Lorence chuckled.

But that doesn’t mean botanical illustrations are less demanding than botanical art. Far from it. While both fields require rigorous adherence to realism and accuracy, scientists like Lorence need work that provides certain contextual information and captures details not necessarily visible to the naked eye.

Although he now works in a field rife with technology, Lorence prefers handmade botanical illustrations to photographs, and does not believe the craft is going anywhere anytime soon.

“I think it’s going to remain a standard requirement or part of publishing a new species … I think it’s going to be with us for quite a while,” he said, with the caveat that molecular tools are now also used to differentiate species or identify new ones.

Editor’s Note: Reporter Scott Yunker works on a casual basis as a gardener in the horticulture department of the National Tropical Botanical Garden.